Erin Lee Carr

Erin Lee Carr has a knack for digging up the fascinating, complex and deeply dark stories found at society’s edges. Erin talks to us about the dual sides of creative success, the inspiring mentorship of her late father, and the hustle she needs to live in New York City …

What brought you to New York?

I moved here seven years ago after living abroad in London, working for VICE Media. I had visa issues—I’m sure you can relate!

It’s literally the bane of my existence.

I kind of said, "Enough.” My family is from Minnesota, but they were living in New Jersey at the time. I asked my dad if I could move home and he said, “You have two weeks at home and then you'll have to find a place." He did not want a kid coming back after college and getting too comfortable. So I moved into a squat in Williamsburg for $500 a month.

Oh my God. I don't think that would be possible to find now.

Actually it's still there. I went to a party there about six months ago. It looks terrible.

Your dad sounds like an amazing motivator!

He was. Luckily, I found work at that time. I was an office PA on the set of Girls—the lowest on the totem pole. Working in that position gave me a very real idea of how many people were between me and those in power. I knew it would take me so long to climb the ladder in that world. So I looked to the documentary world, and saw there were a lot of incredible women in powerful positions. That made the decision for me, professionally. It’s a very entitled thought process. [Laughs]

But it’s also a realistic one.

I was able to get a job at the New York VICE office as an associate producer, which means I was responsible for pitching, researching and assisting producers. I was put on this science-and-tech show called Motherboard, which ended up changing my life because it gave me a niche, a beat, something to explore. It’s a realm that I continue to explore to this day.

It really gave me a framework to look at the world. In terms of storytelling, you can’t get a richer subject matter than science, tech and the Internet. While I loved the job, I still wasn’t creatively fulfilled, so I started shooting a film during nights and weekends about Occupy Wall Street—about the people who were creating a wi-fi tower there, and the police response to it. I showed the film to the people at VICE and they were so supportive. They gave it a screening in New York at the Tribeca Grand Hotel. A door may have been opened for me, but I chose how and when to walk through it. It always comes back to hard work.

Wow, that is incredible.

Opportunities like that are something I’m really looking at now. How much was nepotism involved there? I was 23 years old, and I was given all this freedom and support to create. Was that because of who my dad was?

Your father was David Carr, a highly respected writer.

It's always been this uncomfortable thing that I've had to grapple with. I took every opportunity and I was really aggressive about it, but at the time I didn't see many junior people getting these opportunities, besides at places like HBO or Jigsaw.

It’s not like you didn’t work hard or pay your dues, but you’ll never know how much that was a factor.

Exactly. It’s something I’ve avoided talking about in the past, when giving talks or mentoring young women. It makes people uncomfortable.

So after the airing of your film, how did things change for you at VICE?

I became a producer at VICE. I would say the first piece I produced that became popular was a short video on tardigrades, which are these microscopic space bears. They’re organisms that can thrive in space, but they also exist in moss in West Virginia. The idea originally came from my boss, Santiago Stelley, but it had never been implemented. When we pitched it again, VICE said, “Whatever. Do it. Just don’t spend any money.” [Laughs] We were such a small team, we put it together in just a couple of weeks. It went on to get 10 million views.

And then “Click, Print, Gun” happened, which was a short documentary on this guy who was 3D-printing guns and open-sourcing the blueprint. VICE recognized that I was able to tell these stories that would hit a nerve.

You were bringing in the views!

Plus keeping the production super cheap. We kept the same small team—it was amazing.

Why do you think those two videos hit such a nerve?

They are about two very different subjects, but they both touched on human experience. The tardigrades was about how our experience as humans relates to these tiny little organisms. “Click, Print, Gun” touched on fear. It hit a cultural nerve, which is really important when you’re creating video for the Internet. You want people to react to it and to share it.

How did you move from short videos to your first documentary for HBO?

After awhile I left VICE, and worked briefly at a media company called Vox. I was making content for Vox’s tech site, The Verge. It wasn’t a great fit for either of us. I was in a weird space; I didn’t know what my next step was.

“Ask successful people about their mistakes and what they learned from them. You almost always get an amazing story, and you get to learn from their missteps.”

Why did you leave VICE?

It's the same reason why many people leave their jobs: money. Looking back, I could have handled myself a lot better. I was like, “Bye, I’m going to go make a lot of money now.” Then it was a reality check when I didn’t have my amazing VICE team. It was a hard time in my career.

I was having lots of coffee meetings with filmmakers and people in the industry. I met with an incredible filmmaker, Andrew Rossi, who said to me, "I don't think you should work for a company. I think you should make your own movies." The thought had literally never occurred to me.

He was like, "Okay, we're going to pitch a tech story to Sheila Nevins, the head of HBO Documentary Films.” I had an idea for a feature about the deep web, and she instantly said it was terrible. I was totally crushed! But we ended up talking for two hours, and the story of the “Cannibal Cop” [former NYPD officer Gilberto Valle] came up. She said, “I don't like your ideas, but I like you. See what you can find."

You ended up making Thought Crimes—like the gun documentary, this story also taps into many people’s fears.

Exactly. Andrew and I got a development deal for the project. When we started development, Gil Valle was in federal prison. There is zero chance of getting a camera in there. But a federal judge overturned his conviction—which literally never happens!—and he was let out. That was the turning point for the project, because suddenly, I could try to talk with him. Initially he said, “I was in solitary confinement. I don't want cameras in my face." I called my dad to explain what was happening. I said I was just going to let him be for a couple of days. My dad was like, "Absolutely fucking not, you're going to get a camera. You're going to go over there. That is what your job is. If you don't get that, the movie's not going to get made. Somebody else is going to scoop him." So I pushed Gil for an interview to show HBO, which would decide whether the movie was going to happen. It was terrifying. I was down to my last $500; I needed this to work. I just needed to prove to HBO that I had access to him, that I could get interviews and information. When they said it was green lit, that was the happiest day of my life.

How long did it take you to make that film?

Six months after it was green lit—which is so quick, it’s unheard of. Financially, I was still paying the bills with freelance work during that time.

How did you feel when it was released?

It was an upsetting time in my life. My dad had just died, and I had to do interviews and press. Gil didn’t like the film, either, so that was horrible. It was a crazy, horrible, stressful time. I don't have a ton of memories from that time period.

HBO took really good care of us, but I couldn’t enjoy anything. Everything tasted like ash.

Did your dad get a chance to see the film?

He did. He was really proud when he watched it. I still have his notes and feedback on it.

How do you stay impartial when making a film like that?

It’s really tough. When we were filming, I thought I was impartial—but I wasn’t. The editor Andrew Coffman really helped me see that. It’s interesting to see somebody edit something in a completely new way. My dad always said to surround yourself with the smartest people. I accomplished that with my team. We all felt conflicted by the film, and by the subject of it.

How did it feel when Gil said he was unhappy with how he was portrayed?

Bottom line, he was incapable of taking responsibility for what he did do that led up to his arrest. He said, time and time again that it was meaningless fantasizing, but he toed the line between thought and crime. I didn’t think he ever belonged in jail but I don’t think he was the man he made himself out to be. After the film aired and he made clear he did not like it, he kept texting me and I felt really small and defeated, especially after my dad died. But I'm like, “Fuck that, I won’t let any dude silence me.”

Out of it all came a good lesson. My job as a documentary filmmaker is to seek truth. I have to be really careful with promises and boundaries.

Your new documentary feature for HBO, Mommy Dead and Dearest, was just released.

I was really lucky. We got a great review in the New York Times for Thought Crimes, so HBO wanted to keep working with us and offered another development deal. We started looking into why people confess to crimes online, and that led us to the story of Gypsy Rose Blancharde for Mommy Dead and Dearest. The story only came into the public sphere after BuzzFeed published an article about it.

The story is insane. You can’t make something like this up!

Yes. After Gypsy Rose was convicted of murdering her mother, I was the first person to interview her in prison. We’d gotten footage of her family members, lawyers, and doctors, and we thought it had the potential to be a film, but we really needed to see and speak with her. The film couldn’t have been made without her involvement.

You’ve been promoting this film over the past few months. Are you able to enjoy the process more this time?

Yes. All my family came to SXSW to support me—it’s been spectacular. The film has gotten a couple of great reviews. At SXSW, there was almost a frenetic energy surrounding it. James Franco asked to come to a screening!

What are you working on now?

My third documentary for HBO. I can’t really talk about it yet, but it’s in the true-crime sphere. I’m also working on a book about my dad, and an episode of a series for Netflix.

That’s amazing. Looking back to when you were an office PA, do you feel like you’ve gotten to where you wanted to be now?

Beyond that. I have a note stuck above my light switch at home, which says, “You are living the life of your wildest dreams.” When a day is hard, when I’m scared to talk to someone or feeling fearful, I try to think about that and be grateful.

That’s not to say that it all won’t disappear tomorrow. You know what I mean? That’s what’s really scary about this. I don’t know any other women my age that are making feature docs. It’s really a financially difficult business, and I’m still hustling now. You have to keep working.

Being on set and making these films, I have to be one of the hardest working person there. I am the person that stays late, starts early, gets the work done. So that when somebody is looking to make a film, I’ll be the person they want to work with. That was the mantra in my family: You can be anything in the world, but you can’t be lazy.

That’s especially true in New York. If you can’t afford it, you get kicked off the island. [Laughs] You have to work hard, you have to hustle. I remember asking my dad to borrow money and he was like, “That’s a hard pass.” He wanted me to figure it out. I was freelancing a lot at the time to make ends meet. When I couldn’t get freelance work in film, I would babysit and do odd jobs.

I think I have a little bit of antagonism towards people who are independently wealthy, documentary filmmakers who basically have a glorious career because they don't have to worry about income. I have a lot jealousy, but I’ve been incredibly fortunate to be able to make films that are based on my ideas. That’s not to say I won’t make things based on other people's ideas in the future, or work for a company again. As I said, this can be taken away immediately. I don't take that for granted.

What’s the best piece of advice you could give?

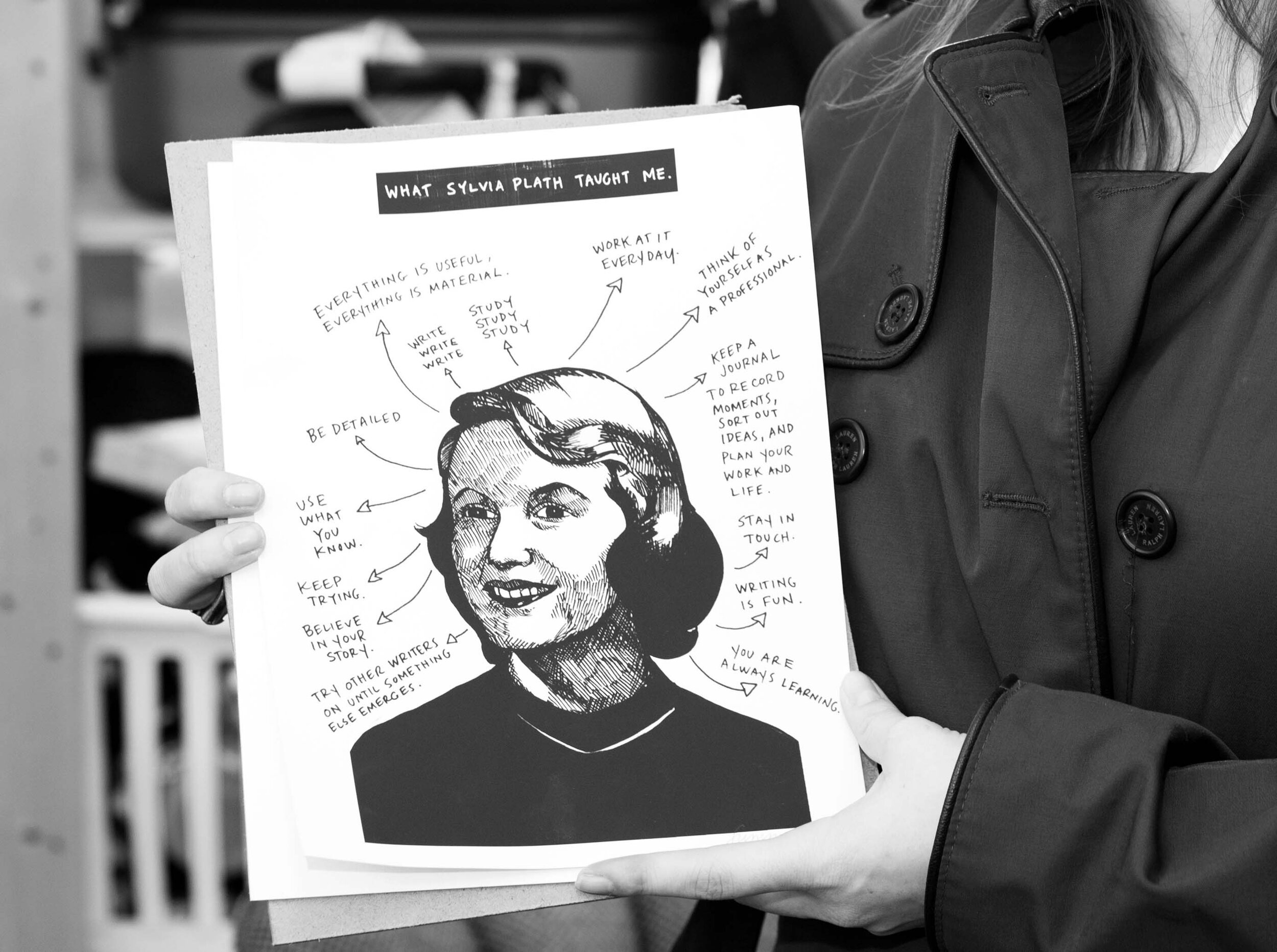

I have an amazing list of all the advice my dad has given me. There are little notes scattered around the office here. I’ve mentioned this one already: Work with the smartest people. A lot of people think the opposite; they want to be the best in the room. I want to be the dumbest in the room! I want to learn from people and be around brilliant individuals.

Also: Ask successful people about their mistakes and what they learned from them. You almost always get an amazing story, and you get to learn from their missteps.

What does New York mean to you?

I have a lot of feelings about New York. I get jealous of space, and people who have a lot of physical space. I get a lot of feelings about weirdos on the subway, about having to commute an hour to the our offices… daily things like that. But then I also realize that none of the things that have happened to me, things that I’ve achieved, could have happened outside New York. You have access to so much here. There is a magical realism to New York. People get shit done here.

Photography by Stephanie Geddes ©